History

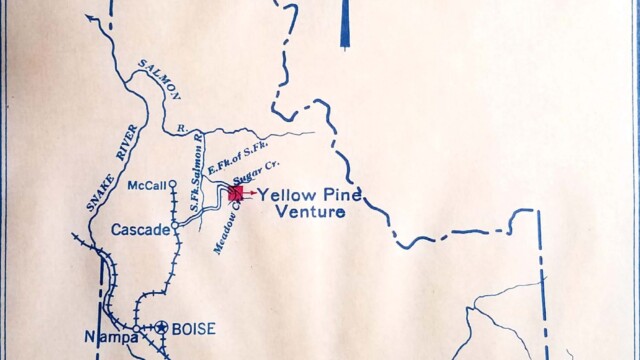

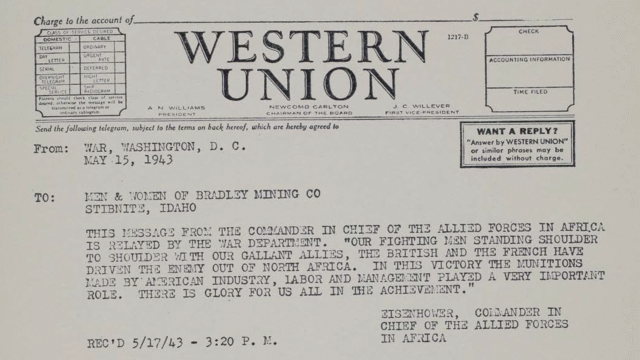

The Stibnite Gold Project site is located in one of the most historic mining districts in all of Idaho. It has been home to thousands of miners, operated by several different companies and was critical to the U.S. war effort in the 1940s and 1950s. After many decades of mining, Stibnite is still rich with minerals but also in much need of environmental repair.

See Stibnite's history in the photos below.

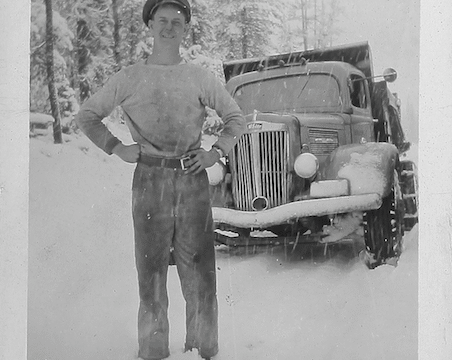

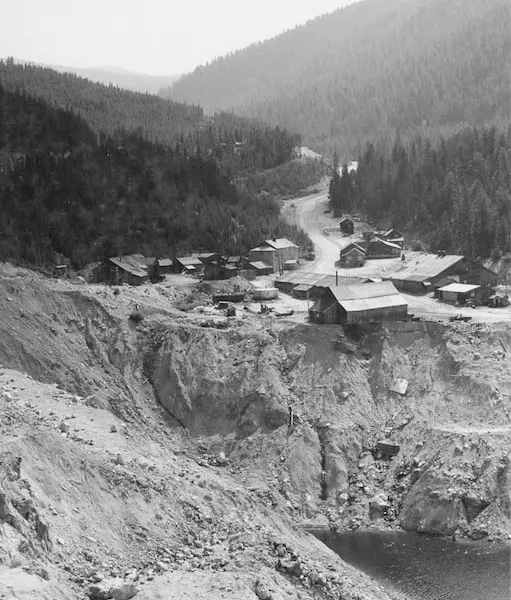

1930

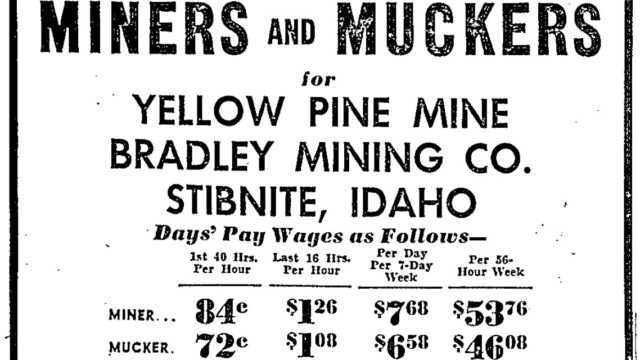

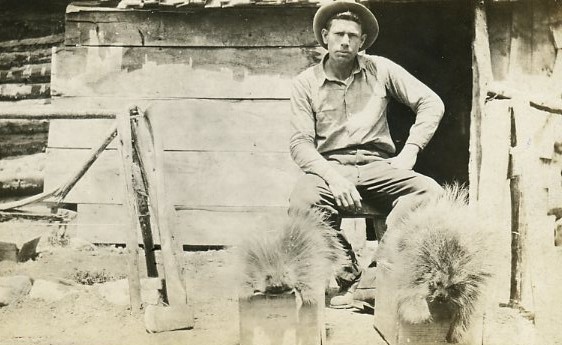

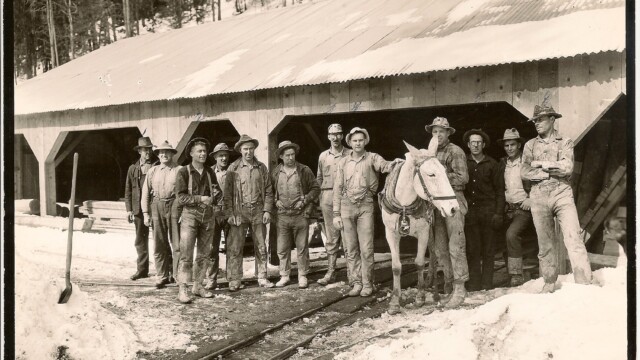

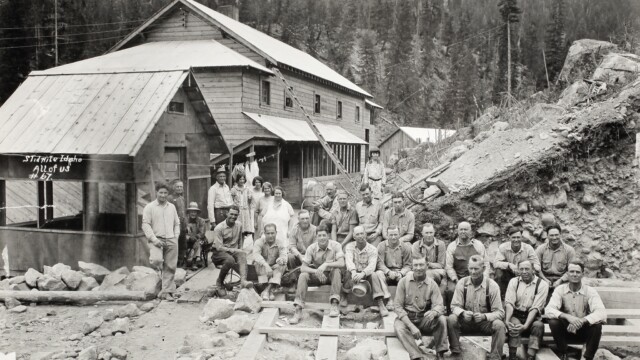

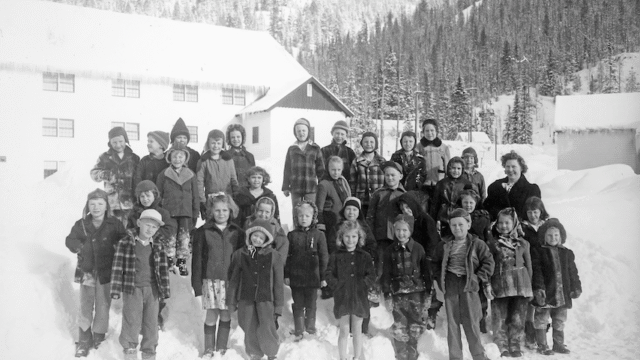

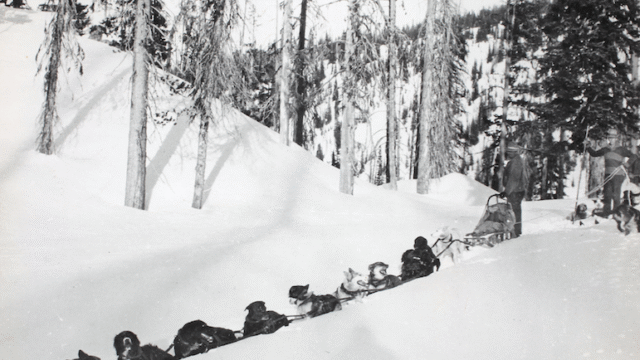

1930 Miners flocked to the region to work for the multiple companies operating in the Stibnite-Yellow Pine mining district.

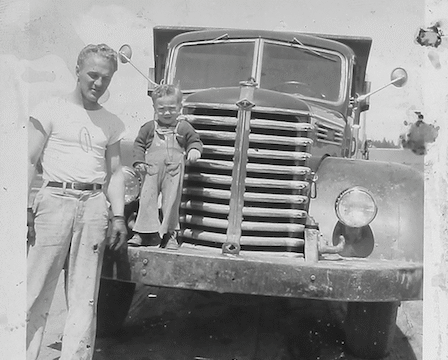

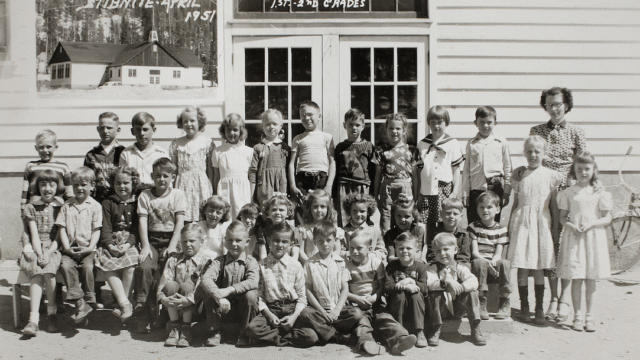

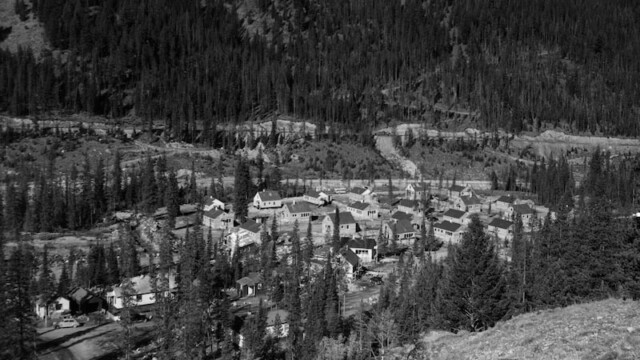

1950

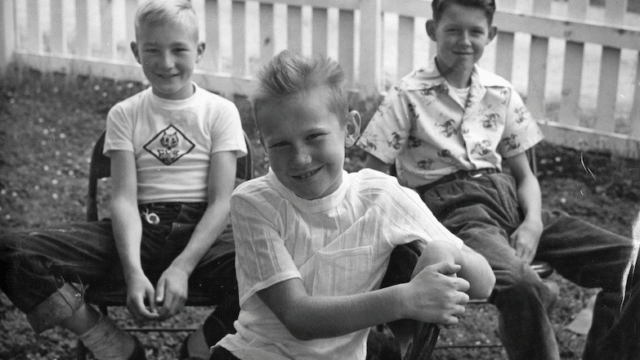

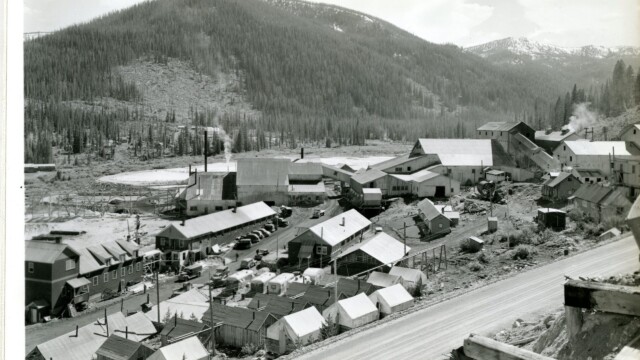

1950 The town of Stibnite grew significantly when the US Government declared antimony as a critical mineral for the WWII effort.

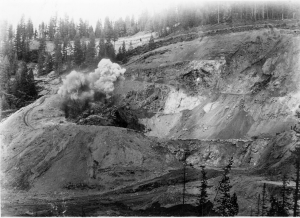

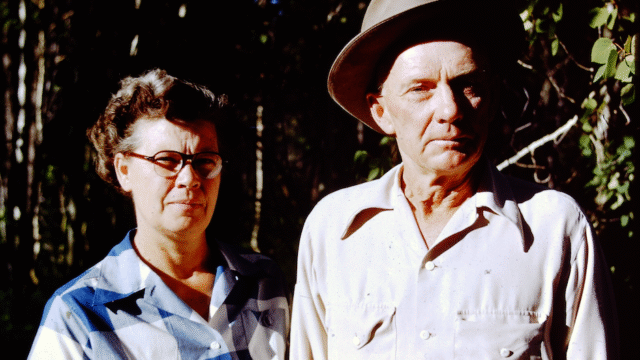

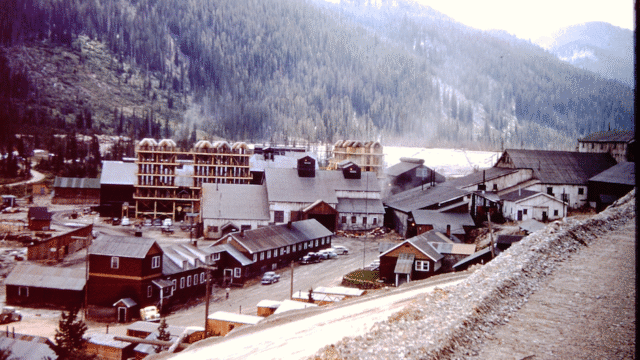

1960

1960 After the war years, many of the original structures were dismantled and people moved out of Stibnite.

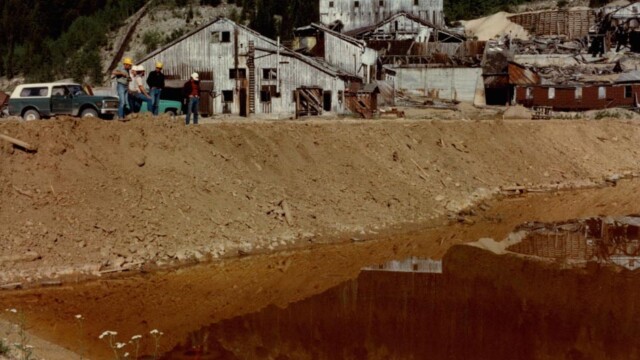

1965

1965 From 1959 to 1965 an estimated 30,000 tons of sediment erode into the Salmon River.

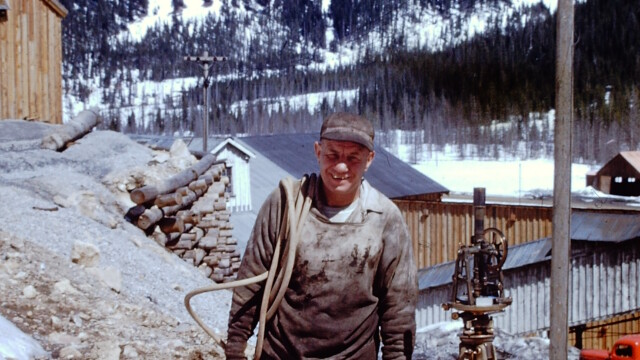

1996

1996 Active mining restarted in the 1970s and continued sporadically until the 1990s.

2015

2015 We are currently studying Stibnite's environmental needs to develop the best plan for mining and restoration.

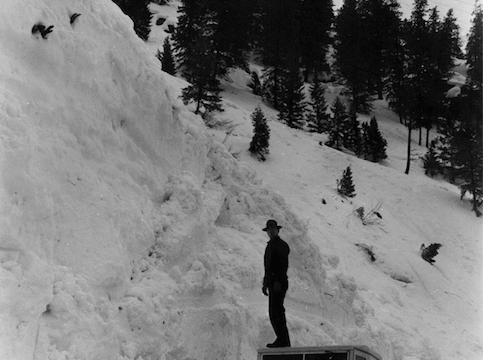

Meadow Creek Mine and Mill

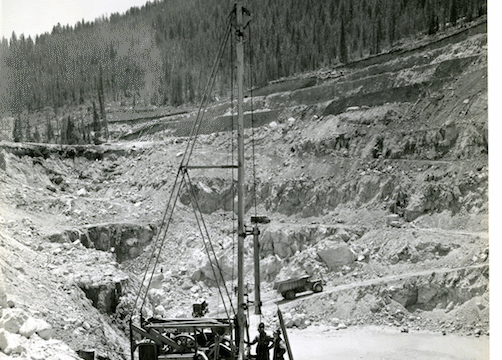

Albert Hennessy discovered antimony-gold mineralization and staked the first Meadow Creek claims in 1914. Limited activity followed prior to 1927 when development of the camp, roads, hydroelectric and milling operations increased greatly. By 1932, the underground Meadow Creek Mine was a significant operation with more than 80 men working on the mine, mill and ancillary facilities year-round. By 1938, this mine produced more than 50,000 ounces of gold, 180,000 of silver, and many tons of antimony. During the period from 1932 to 1928, the Meadow Creek Mine was the second largest gold producer in Idaho and was by far the largest operation in Valley County. Underground workings extended more than 500 feet below the ground surface. In 1938, the underground mone was abandoned in favor of the recently opened Yellow Pine Pit.

The Bradley Mining Company mill remained in this location even after the underground mine closed. The mill was a pioneer in the use of a floatation process to recover gold and antimony and, later, gravity recovery of tungsten. In 1941, the mill switched to a flotation process for tungsten in order to improve recoveries. For several years in the mid-1940’s this mill produced approximately half of the U.S. tungsten supply and up to 90% of the antimony for the war effort. A smelter was completed in 1949 to avoid the expense of trucking concentrate to the rail facility in Cascade. The mill shut down in 1952 and, by 1958, had been dismantled. Up to 1958, total production for the District (from both Meadow Creek Mine and Yellow Pine Pit) totaled more than 405,000 ounces of gold, 88 million pounds of antimony, 1.5 million ounces of silver and 13.5 million pounds of tungsten.

A second generation of miners (Canadian Superior, Pioneer Metals, Stibnite Mines, Inc., etc.) operated in the district from late 1978 to 1996. Their process plant and on-off heap leach pads were located immediately northeast of the former Bradley mill site. The still-visible heap consists of neutralized ore left by Hecla Mining Company. This ore came from the Homestake area of the Yellow Pine deposit. Production from all operators during this second generation is estimated at more than 581,000 ounces of gold and 149,000 ounces of silver.

Perpetua Resources’ Hangar Flats mineral resource encompasses the former Meadow Creek mine and mill site and the Hecla heap.

Meadow Creek

In the absence of modern environmental knowledge and regulation, and later to meet wartime demands, the first generation of miners at Stibnite placed mill tailings wherever they could in the Meadow Creek Valley. When the mill was expanded in 1946, Bradley Mining Co. considered moving the mill closer to the Yellow Pine pit, but this idea was discarded as they could not find a more suitable tailings repository. In the end, Meadow Creek was diverted and a 171-acre storage area was set aside for tailings placement.

By the time Bradley ceased operations in the 1950’s, more than four million cubic yards of tailings had been placed in the upper valley. In 1959, government officials ordered Bradley to breach the tailings containment and Meadow Creek flowed through, rather than around, the tailings. Over the next 20 years, an estimated 10,000 cubic yards of tailings were eroded by wind and water and washed downstream into the East Fork of the South Fork of the Salmon River system.

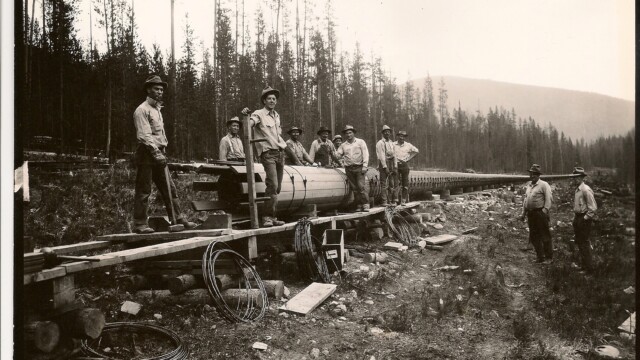

Across the valley, the East Fork of Meadow Creek (a.k.a. “Blowout Creek”) was the site of Bradley’s hydroelectric reservoir. Constructed in 1931, water from the reservoir entered a pipeline to generate power in the valley bottom. A 28-inch diameter redwood pipeline also conveyed water from the town site pond to a power house at Sugar Creek. In 1965, the dam was breached by government officials, leading to erosion and the scar you see now. Blowout Creek remains a major source of sediment in local surface water, and erosion in the lip of the valley above has resulted in falling water tables in the Blowout Creek Valley, reducing wetland quality.

By 1978, a later operator in the District (Canadian Silver) undertook several remedial actions, including diverting Meadow Creek around the tailings and encapsulating the tailings with more stable spent ore and waste rock. By 1994, six million cubic yards of spent ore had been placed on top of the historic tailings, creating the Spent Ore Disposal Area (SODA). In the late 1990s, Meadow Creek was moved again to the current diversion channel and, in the 2000s, the Forest Service conducted additional remedial actions along lower Meadow Creek and in the former mill site area,

Should Perpetua Resources earn the right to mine the District again, the historic tailings would be reprocessed and placed in a modern, lined facility along with new tailings from Perpetua Resources’ mill. In addition, spent ore in the SODA area may be utilized for construction purposes, reducing the need for mining of fresh aggregate.